from Indian Country Today August 19, 2015

from Indian Country Today August 19, 2015

By Jon Magnuson

Twenty years ago, on a visit to Great Falls, Montana, I spent an afternoon casually wandering through the C.M. Russell Auction of Original Western Art, reputed, at that time, to be the most prestigious Western art show in North America. Periodically, I’d stroll down a few streets to a conference room at a local motel where the 10th Annual Montana Native American Art and Craft Sale was being sponsored by regional tribes.

The contrast between the two couldn’t have been more dramatic if it had been scripted by Hollywood. At the Russell exhibition, the main show room was packed with vendors and well-heeled tourists. The upscale venue was filled with hundreds of perfectly executed, over-the-top depictions of American Indians on horseback, picturesque village encampments in mountain meadows, and sexualized, doe-eyed young Native maidens clothed in traditional ceremonial buckskin.

Not far away at the Best Western, the majority of the forty-some Native artists displaying their work in a modest conference room were nonprofessionals. Among them were a dozen teenagers showing beadwork and paintings. One of the organizers, a local leader among the Blackfeet, stood up to share remarks. “Last year,” she said, “Montana’s governor stopped by our show and bought a piece of art. He said he’d mail us a check. We told we’d let him take the art and would even write him a temporary receipt. The problem was,” she said, her eyes twinkling, “when it came right down to it, none of the Indians at the table knew his name.”

In 1988, a few years before my visit to Great Falls, Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. We know now it was to become the 20thcentury game-changer for Indian country. Stereotypes about Native Americans still dominate, of course, the contemporary American cultural landscape, but these days “casino land” is the first image that pops up for the majority of the public. A second, thanks to the influence of Seattle photographer Edward Curtis and upscale art galleries on Santa Fe’s Canyon Road, remains the feathered warrior on horseback. A close third, the butt of dismissive jokes, is the drunken, homeless street bum living off federal aid.

The path ahead is unclear. Identity, for most Indian people, in the first part of the 21stcentury as never before, will be carved out, collectively and individually, from a swirling world of carpetbaggers, do-gooders, and self-serving politicians and missionaries, many who are predators, economically and spiritually, across Indian Country. No one is going to turn the clock back, but there will be decisions, perhaps more important now than ever, to be made by tribes. They will define the future for generations to come. And those decisions will be about money and soul.

There’s no question that the economic prosperity resulting from the gaming industry legal agreements between tribes, states and the Federal government, has been nothing less than an historic, cultural landmark. But tribal efforts to protect traditional spiritual and cultural values will increasingly become the real battleground unless we’re all satisfied to watch what’s left of a treasure of North American indigenous culture sink into Donald Trump’s Wall Street Nirvana, a cesspool of consumer-driven, materialistic mindlessness.

It should not be, I’m suggesting, a choice between money or soul. There’s nothing wrong with a healthy tribal income from the casino industry. That is, as long as a significant portion of that income can be set aside by tribes to fight intrusions of irresponsible mining companies, short-term forest harvesting practices, and profit-driven corporate polluters. With a priority of protecting the sanctity of natural resources on Treaty lands, American Indian peoples will recover and claim their rightful place as original custodians and defenders of our land, our air and water.

Here in a remote part of Northern Michigan, the heart of such a vision is emerging in a collaborative effort by five tribes to preserve what remains of the original “ecological footprint” of plants and pollinators. Tribal communities are working together to establish centers for environmental education, field training, and promotion of Native seed harvesting and butterfly/bee protection. Those efforts are intentionally framed by ceremony and Native traditional spiritual teachings.

The test is a real one. Harvesting of wild rice, processing of maple sugar, and the growing of ginseng hold extraordinary and untapped potential revenue for tribe-based economies. If such intentional investments can be sustained, they will certainly outlast and, with the selected promise of global markets, even one day possibly outcompete revenues from blackjack tables and slot machines.

Meanwhile, tribes like the Lummi in Northwest Washington State, the White Earth and Fond du Lac in Minnesota, Bad River in Wisconsin and the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community in Michigan serve as examples where collective voices, fierce and visionary, are finding allies to confront some of the largest international companies in the world in order to protect threatened national resources. These same communities, along with Michigan’s Hannahville, Lac Vieux Desert, Bay Mills, and Sault tribes, are building tribal economies around renewable natural resources, protecting and preserving what is left of rare plants on their own tribal lands.

Keweenaw Bay Indian Community Native Plant Greenhouse

Be assured. There are those of us, prepared and ready to join you… churches, nonprofit organizations, and individuals working in federal agencies… so we can together, in prayer, dance our way into a collaborative spiritual way of caring for Mother Earth that this planet we all call home has never seen before.

Jon Magnuson is a former Peace Corps volunteer and currently Director of The Cedar Tree Institute. He coordinates, along with Jan Schultz, a US Forest Service Botanist, and five tribes in Northern Michigan, the Zaagkii Project (www. wingsandseeds.org), a Native plants and pollinator protection initiative. In 1987, while serving as ELCA Lutheran pastor at the University, he drafted “The Bishops Apology” with the Church Council of Greater Seattle, a document pledging support to 46 tribes of the Pacific Northwest for helping recover, restore, and protect traditional Native American spiritual teachings.

from

from

On Tuesday morning, May 26, 2015 a traditional offering of tobacco and cedar was scattered on the waters of Lake Superior by 14-year-old Kayla Dakota to mark the beginning of a second trip by KBIC tribal youth to visit one of the most remote, isolated National Parks in North America. The first KBIC youth expedition to Isle Royale took place in May 2013 aboard the 36 ft. research vessel “Agassiz.”

On Tuesday morning, May 26, 2015 a traditional offering of tobacco and cedar was scattered on the waters of Lake Superior by 14-year-old Kayla Dakota to mark the beginning of a second trip by KBIC tribal youth to visit one of the most remote, isolated National Parks in North America. The first KBIC youth expedition to Isle Royale took place in May 2013 aboard the 36 ft. research vessel “Agassiz.”

THURSDAY

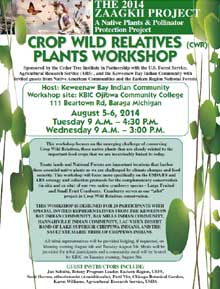

THURSDAY August 5-6, 2014

August 5-6, 2014

June 2-3, 2014

June 2-3, 2014

Karen Anderson at the 13th annual North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) International Conference highlighted native plant and pollinator work by the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC) Natural Resource Department and the Zaagkii Wings and Seeds Partnership on October 22-24, 2013. Karen, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community Natural Resources Department Plant and Greenhouse Technician, made a presentation at the NAPPC event in Washington D.C.

Karen Anderson at the 13th annual North American Pollinator Protection Campaign (NAPPC) International Conference highlighted native plant and pollinator work by the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC) Natural Resource Department and the Zaagkii Wings and Seeds Partnership on October 22-24, 2013. Karen, Keweenaw Bay Indian Community Natural Resources Department Plant and Greenhouse Technician, made a presentation at the NAPPC event in Washington D.C.